To Catch a Tartar: A Dissident in Lee Kuan Yew’s Prisonis an excellent study of the conceit and deceit of a man many Singaporeans thought they knew. The author, Francis Seow, is a former solicitor general and president of the Law Society in Singapore. This is his first-hand account of how he has suffered under the PAP government’s use of biased legislation and media manipulation to maintain political hegemony.

In Devan Nair’s words, Seow’s book is an eye-opener, “for those whose eyes still require to be opened”. The former president of Singapore, who incurred the “implacable wrath of a political genius gone awry” [referring to Lee Kuan Yew] for his public defence of Francis Seow, was labelled an alcoholic in a White Paper tabled before the Parliament.

Despite that, Nair traded blows with the government in several hard-hitting press statements and included a scathing attack on Lee in the foreword of this book: “Today, Lee no longer deals with his equals, but with his chosen appointees, who did not earn power the hard way, but had it conferred on them. They are highly qualified men, no doubt, but nobody expects them to possess the gumption to talk back to the increasingly self-righteous know-all that Lee has become. Further, the bread of those who conform is handsomely buttered. Keep your head down and you could enjoy one of the highest living standards in Asia. Raise it and you could lose a job, a home, and be harassed by the Internal Security Department or the Inland Revenue Department, or by both, as happened to Francis Seow.”

Such unsavoury opinion of Lee was shared by Seow, who wrote: “The passage of years, far from mellowing the prime minister, has made him more imperiously intolerant of the common man. His abrasive, intrusive style of governance has not changed, and is best exemplified by this statement, brimming with his customary, boastful insensibility, in the Straits Times of 20 April 1987: ‘I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn’t be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters – who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think.’”

Referring to Lee’s brutal treatment of Nair, Seow lamented “there are, regrettably, very few Singaporeans with that rare courage and intellectual, let alone political, honesty to call a spade a spade”.

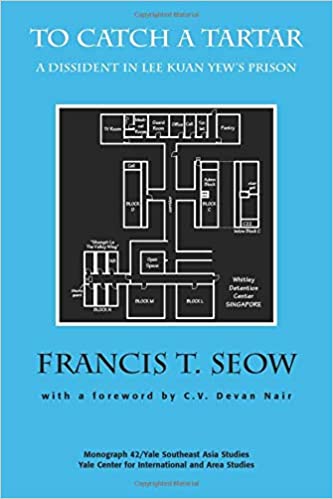

On his part, Seow’s account of the horrendous process of interrogation he underwent at the Whitley Detention Centre includes disturbing dialogues like the following utterance by an Internal Security Department (ISD) officer: “Look, cut out all your court English. This is not a court of law. The rules of evidence do not apply here. We make the rules here. This is a kangaroo court. No one can help you, no one. All the human rights organisations can do is make a little noise, but how long can they keep it up? After a while, you will be forgotten.”

This devious way of thinking was also evident at the press conference following the arrest of the supposedly Marxist conspirators, which triggered off a chain of events leading to Seow’s subsequent detention. When asked by Archbishop Gregory Yong for proof of the involvement of Vincent Cheng, et al, in clandestine communist activities, Lee interjected with a sharp disclaimer, “I have never said that I was going to prove anything in a court of law”, which left his audience stunned. He continued: “It is not the practice nor will I allow subversives to get away by insisting that I [have] got to prove everything against them in a court of law or evidence that will stand up to the strict rules of evidence of a court of law.”

Contrast this to what Lee said during the Legislative Assembly Debate on 15 September 1955: “If it is not totalitarian to arrest a man and detain him, when you cannot charge him with any offence against any written law – if that is not what we always cried out against in Fascist states – then what is it?”

This, and several other quotes of Lee’s speeches in the 1950s and 1960s, were cleverly used by Seow throughout the book to show how Lee has become almost everything he used to be against since he came into power.

Seow also quoted to potent effect a comment by Jerome A. Cohen, a prominent legal representative of Asia Watch, who found deeply disturbing both the use of psychological torture and what he called a pervasive Singaporean, if not Asia view that “if you haven’t hit somebody, it isn’t torture”.

Seow’s description of his harrowing experience during detention seemed to have confirmed Cohen’s observation: “He [an ISD officer] swung his hand at me. I braced myself for the blow. But his fist stopped short just inches from my face. He looked like a thug. He behaved like a thug. He was a thug. …. Amidst deafening obscenities, he swaggered up to me and repeatedly blew thick clouds of cigarette smoke into my face. … Venting his frustration at my continued silence, he demanded that I take off my shirt leaving my upper body bare under the air-conditioner duct. No one stopped him. I reluctantly complied. It was cold. Very cold. Very very cold.”

Later in the book, Seow described the ISD’s tactics as such: “The word ‘torture’ normally evokes visions of medieval cruelty and violence, of racks, thumbscrews, and other exquisite instruments of pain and suffering. But the prime minister’s version of the Spanish Inquisition is more subtle and no less effective. A detainee can be made to admit anything by the simple expedience of prolonged deprivation of his sleep – a most effective weapon in the ISD armoury of persuasions, which is its standard procedure.”

The author also highlighted some of the dirty tricks used by the ISD: “For years, the conference room of the Barisan Sosialis headquarters was wiretapped without the leaders being aware of it. And the bugging of the residence of Barisan Sosialis’ chairman, [the late] Dr. Lee Siew Choh, was only discovered when workmen accidentally found the bugging device above the ceiling of the dining room whilst making repairs in his home.”

Seow further opined that the so-called Marxist conspirators were really just a group of young, intelligent, and idealistic graduates who could give the Worker’s Party credibility and status if they were to enrol as members. But, according to Seow, it was crucial, using officialdom’s favourite metaphor, to “nip them in the bud” before the flowers could bloom and contend.

To Catch A Tartar is thus a sober reminder that power, if left unchecked, can have dire consequences. Make sure you read Nair’s open letter to Lee at the back of the book for an intriguing insight into some historical events in Singapore.

Conclusion: A gripping tale of how Lee Kuan Yew systematically and ruthlessly roots out and destroys any form of dissent in Singapore. Viewed in that perspective, the plight of Ryan Goh, the SIA pilot who was evicted from Singapore over the Alpa-S incident, is hardly surprising.

A price too high to pay?

Wednesday • August 17, 2005

Siew Kum Hong

news@newstoday.com.sg

MANY Singaporeans would have been disappointed last Sunday morning, when they woke up to the news that President SR Nathan will be re-elected without a contest this week. Few would have been surprised, after last week’s damaging statements from JTC Corporation, Hyflux and United Test and Assembly Centre (UTAC) about Mr Andrew Kuan.

The events surrounding Mr Kuan’s abortive bid for the presidency have raised questions about the institution and the legitimacy of future office-holders.

After Mr Kuan announced his candidacy, various political figures spoke out on his bid. Their comments either touched on Mr Kuan personally or on the office of the presidency. Some, such as MP Charles Chong, chairman of the town council that Mr Kuan serves in, questioned his qualifications. Several unidentified persons described him as “arrogant” or “conceited”.

Meanwhile, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office and Second Minister for National Development Lim Swee Say warned against the consequences of a fluke result, citing the Chinese saying, “Don’t fear 10,000, only fear the one-in-10,000 chance.”

Others focused on the “seriousness” of the office and the need for the President to be the face of Singapore to foreign dignitaries, as if implying Mr Kuan had been judged and found wanting. There was also a call for him to be more transparent on his career history.

Most of the comments came even before JTC (and, to a lesser extent, Hyflux and UTAC) came forward and hammered nails into the coffin of Mr Kuan’s aspirations.

Just as disturbing was the fact that all the comments came before the Presidential Elections Committee’s (PEC) decision on Mr Kuan’s eligibility. The latter had come under intense scrutiny even before he officially became a candidate.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the establishment felt discomfited, if not threatened, by the sudden appearance of a possibly credible candidate not endorsed by it. And judging from Internet postings (admittedly a lopsided barometer of public opinion), I am not the only one who felt so or who was bothered by this.

The role of the media was also troubling. Mr Kuan’s candidacy was effectively subject to a trial by media. The politicians’ comments were invariably given prominence. I think JTC’s decision to release a press statement and hold a press conference disclosing their decision to ask Mr Kuan to leave, while declining to go into their reasons or the details of their report to the PEC, effectively used the media to destroy Mr Kuan’s chances.

Furthermore, as the reason for its decision, the PEC gave a bare assertion that Mr Kuan’s position as JTC group CFO was not comparable to the requirements under the Constitution. It did not explain in detail its reasoning in arriving at this conclusion.

It is therefore unclear what role was played by the crucial JTC report or whether the PEC had taken into account the various statements and disclosures in the media. It is also unclear whether the PEC should have interpreted the Constitution so as to err on the side of caution by allowing a contest in the interests of transparency and legitimising the presidency.

What happened with Mr Kuan’s candidacy will be remembered for a long time to come. And this is where the presidency may have been damaged.

The requirements for a president are so stringent that the pool of eligible candidates is nothing less than miniscule. They will inevitably be people of substance and means. So why would they want to subject themselves to the storm of criticism that Mr Kuan experienced, which recent events would have shown to be the likely consequences of a candidacy not endorsed by the Government?

This unendorsed candidacy is precisely what is needed. The elected presidency was conceived as a check on a rogue government. In my view, people could become sceptical if only candidates endorsed by the government of the day can become President.

Yes, whoever becomes President should be suitably qualified. But that is for the PEC, not the government of the day, to decide.

Even Mr Nathan recognises that a true contest (as opposed to one engineered by the Government, as in 1993) may be necessary for legitimacy in the people’s eyes. At the very least, it must be possible for a candidate not endorsed by the Government to mount a viable bid. But if the personal price of running is seen as too high or the odds perceived to be stacked against an independent candidate, then nobody will step forward.

And so, in trying to ensure that Singaporeans do not inadvertently elect a President who is not up to the job, our leaders may have — equally inadvertently — ensured that the elected presidency will forever remain a misnomer.

The writer is a lawyer commenting in his personal capacity.

While Lee Kuan Yew collaborated with the Japanese during occupation, most other Chinese in Singapura suffered.

They were tortured and killed. And Lee Kuan Yew benefited himself by working for the Japanese propaganda department and supplied and built for the Japanese military.

The same military that killed thousands of Chinese in Singapura. In this, we need to empathise with the Chinese community for the brutality heaped upon them in Singapura.

The brutality is known as Sook Ching.

Sook Ching refers to the wartime massacres conducted by the Japanese military during World War 2. In Singapura, it is estimated that 10-20% of the Chinese adult male population were killed during this genocide.

Japan had been at war against China for several years. And the Chinese community in SIngapura had raised funds for the Chinese war effort.

Soon after taking control of Singapura, the Japanese military launched the Sook ching operation.

As written by Geoffrey Gunn,

"Summary executions and other punishments, such as the placement of decapitated heads of looters in Fullerton Square (ex-Singapore GPO site), were just an early foretaste of what would transpire…"

Four professionals, Wan, Lai, Tham and Wang, who had escaped Singapura soon after the British collapse related what happened:

"When the enemy entered Singapore, the first day they killed over 5,000 of our people. On the second day they divided Singapore into several sections or districts and got all the people out of houses into the streets for the purpose of checking.

They were left in the open road for [three] days and three nights without food or shelter. Five men were chosen by the Japanese to scrutinise the people and to find out if they were anti-Japanese or not.

These five men stood with faces covered on the table and by simply nodding the head send the people to their fate. Once the people were passed they were stamped with a mark on the face, on the body, on the clothes and so on.

Then over 50,000 young men and women were taken away to an unknown destination. What has become of them nobody knows. Out of these people not a single one has come back.

The Japanese soon arrested all the Chinese leaders and beat them heavily and Mr. Boey Ki Hong was killed outright by this murderous beating.

They then asked the leaders to form a Peace Society and forced the Chinese community to contribute $10 million to support the Japanese. Raping and looting were common scenes."

"Various accounts have identified the major killing fields as the then remote Changi beach, Punggol… Bedok and other sites. As widely understood, the Changi killings were execution by machine gun with bodies dumped into the sea."

The Japanese military…the brutal oppressors that Lee Kuan Yew collaborated with.

Gunn, Geoffrey C. "Remembering the Southeast Asian Chinese massacres of 1941-45." Journal of Contemporary Asia 37.3 (2007): 273-291.

Pingback: The bogeyman is among us - Mindblogging Stuff